Sunday, October 28, 2007

Peer Popularity: Understanding Social Dynamics of Peer Relations

What is Peer Popularity?

In order to understand what makes someone popular amongst their peers, we must first define what it means to be popular. Research suggests that peer popularity can be broken down into two sub categories, they are, peer perceived popularity (also known as consensual popularity) and sociometric popularity (de Bruyn & van den Boom, 2005; Kosir & Pecjak, 2005; Parkhurst & Hopmeyer, 1998). Kosir & Pecjak define socieometric popularity as “students who are well liked by many and disliked by few“ (p.129). In contrast Kosir & Pecjak state that students who are perceived as being popular are those who are described as popular by their peers but are not necessarily like.

It is important to distinguish the two forms of popularity, as both forms differ in their characteristics (Kosir & Pecjak, 2005). Kosir & Pecjak also explain that peer popularity differs from peer friendships. The sociometric measures of popularity does not explore one on one friendships, but rather, perceived status or acceptance within a larger group (Kosir & Pecjak).Therefore, the definition of popularity, is not the amount of friends you have or don’t have; it is how you are viewed within a group.

What Characteristics make you popular?

Not surprisingly children who are sociometiricly popular carry likeable personality traits. These children are easy to get along with because they are cooperative, sharing, forgiving and able to keep promises (de Bruyn & van den Boom, 2005). Furthermore they tend not to be mean, dominating or overly emotional (de Bruyn & van den Boom). Lease, Kennedy, & Axelrod (2002) support this view, suggesting that children who are sociometricly popular have higher levels of prosocial behaviour and lower levels of aggressive and disruptive behaviour.

Peer perceived popularity on the other hand is has different characteristics. Lease et al. (2002) claim the peers perceived as being popular have expressive equipment, spending power and are above average in social aggression and social visibility. In addition LaFontana and Cillessen's (2002) study suggests that peers perceived as being most popular were rated at higher levels attractiveness, social connectedness, intelligence and athleticism. This evidence may suggest that popularity can influence perception of favoured personal characteristics or that favoured characteristics can influence perceptions of popularity.

Peer perceived popularity, also has some associations with sexual activity (Prinstein, Meade & Cohen, 2003). Results from Prinstein et al. suggest that higher reports of oral sex were associated with peer popularity, but not likeability. However, if the number of sexual partners increased, popularity decreased (Prinstein et al.). Prinstein et al. claim that being sexually active fits the prototype of being popular. Therefore more students are likely to engage in sexual activity or report that they are sexually active to gain status.

Common characteristics of Sociometric Popularity and Peer Perceived Popularity.

A common characteristic of both sociometric popularity and peer perceived popularity is attractiveness (Boyatzis, Baloff & Duriex, 1998). Analysis suggest, that the perception of attractiveness is related to the perception of popularity (Boyatzis et al.). That is, as perceptions of attractiveness increases so does perceptions of popularity. These correlations were found both within the female population and the male population (Boyatzis et al.). Adams & Roopnarine (1994) supports these findings as they found that facial attractiveness plays an important role in both peer perceived popularity and sociometric popularity.

In addition both sociometric and peer perceived popularity tend to have positive correlations with social competence (Adams & Roopnarine, 1994). However, the 2 subcategories of popularity use their social competencies differently, but, both know how to use their skill to their advantage. For example, those who are perceived as being popular know their goals and how to achieve them, even if it means being aggressive and manipulative (LaFontana & Cillessen, 2002). This is because they are competent in understanding social structures. However, sociometrically popular students use their skills to gain friendships (see Appendix C for examples).

Does not being Popular make you Unpopular?

According to Kosir & Pecjak (2005) those who are not considered popular in school are not unpopular. Popularity should be considered on a continuum, as either being high or low in popularity. As Kosir and Pecjak (2005) state “the absence of acceptance does not imply the presence of rejection, and the absence of rejection does not imply the presence of acceptance” (p.130). Therefore, being considered popular is independent of being considered unpopular (Kosir & Pecjak). We will now explore some of the characteristics of those children who are considered unpopular.

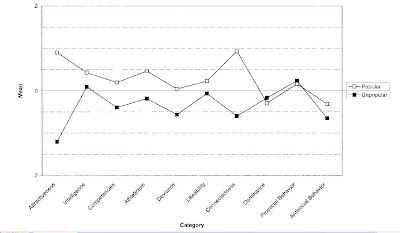

According to LaFontana and Cillessen (2002) students who were considered unpopular had significantly lower levels of favoured characteristics. In comparison to popular people, there were significantly lower reported differences found in attractiveness, intelligence, athleticism and social connectedness (LaFontana & Cillessen). Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of these differences. Generally the children who were considered unpopular had significantly lower measures of desired characteristics than those seen in popular children.

Social Psychological Variables Contribute to Popularity

Groups are formed amongst peers, just like in life, through social categorisation (Baumeister & Bushman, 2008). Those who are considered popular have to maintain their status so they tend affiliate with those who are similar to them. This is because, the people you associate with will influenced how one is perceived by their peers (Boyatzis et al., 1998). Making, Stigma by association an evident dynamic of peer association.

Less popular children seek to join popular groups because they can attain higher status. However, popular children have to reject attempts from others to join their group to avoid stigma by association (Steinberg, 1993). This creates segregation and in-group and out groups structures (de Druyn & van de Boom, 2005). de Druyn and van de Boom suggest that initial likings towards the popular group may became negative because of rejection and jealously. Therefore, the paradoxical idea of popularity is formed (Steinberg).

According to some researchers, children generally have well formed stereotypes about who they consider to be popular and unpopular (LaFontana & Cillessen, 1998). These stereotypes are either confirmed or dismissed depending on personality. For example, those who fit the unpopular stereotype are given less positive attributions by other peers (LaFontana & Cillessen). Therefore, if unpopular children behaviour negatively it further confirms the unpopular stereotype. In addition, less stable attributions were given for more for positive behaviour of the unpopular children (LaFontana & Cillessen).

In contrast the popular children have a mixture of positive and negative attributions towards them from their peers. Popular children are held less responsible for negative behaviours. However, they also had less stable attributions for their positive behaviour (LaFontana & Cillessen, 1998). According to de Bruyn & van den Boom (2005) some of less stable or even negative attributions towards those who are perceived as being popular may be due to judgement, envy or jealousy.

Just like many individuals who interact in a group, children and adolescents over a period of time create group norms and values (Sebald, 1992). These norms can be based on stereotypes but according to Sebald, clothing and appearance is the most predominant group norm. Many students, in particular females, tend to have desires to be more popular (Sebald). Therefore, students are more likely to be susceptible to the normative influences (Bushman & Baumeister, 2008). Sometimes failure to meet the expected norms can lead to rejection or ostracism (Sebald).

Norms are typically created and passed down from earlier generations within the school or are made by the current leader (Bishop et al., 2004). According to Bishop, et al., leaders create norms which reinforce the popularity and authority of a crowd. The popular student leaders are able to control the norms, as other students look up to them to determine what is cool and uncool (Bishop et al). Therefore, the popular students are used as a reference group or an example of behaviours which will maintain ones social acceptance (Bishop et al; Sebald, 1992).

Peers who are perceived as being popular are also considered the trendsetters. They have the ability to integrate cultural dress norms depicted in the media to the school grounds. Therefore, those who are able to create this integration, successfully gain status, prestige and dominance (de Bruyn & van den Boom, 2005). This is an example of how norms from broader society can become norms in the school context and can influence group structures.

McClellands theory of needs might explain some of the social interactions in peer groups. McClellands theory of needs suggests that humans are motivated by three needs (Deckers, 2005). Those needs are affiliation, achievement and authority (Deckers). McCelland’s theory may give some insight as to why these social groups occur in the first place. As identified earlier peer interactions are important to the development of personal identity. Personal identities can be shaped from the attempt to meet these needs in social environments. (See Appendix D for examples)

Conclusion

From the research presented here it is evident that social interactions between children and adolescents are complex. This essay distinguished two different types of popularity and provided a snapshot of what it means to be popular. However, it has not come close to describing the full dynamics associated with peer popularity. Through looking at social categorisation, stigmas, norms, attributions and stereotypes we get a glimpse of the complexity of the popularity system.

Appendices

Appendix A: Glossary of Terms

Appendix B: Paradoxical Popularity

Appendix C: Social Competencies

Appendix D: Affiliation, Achievement & Authority

Appendix E: Evaliation

References

Adams, G. R. & Roopnarine, J. L. (2004). Physhical attractiveness, social skills and same-sex peer popularity. Journal of Group Psychotherapy, Phychodrama & Sociometry, 47(1). 15-36.

Baumeister, R. F., & Bushman, B. J. (2008). Social Psychology and Human Nature (1st ed.) Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth

Bishop, J. H., Bishop, M., Bishop, M., Gelbwasser, L., Green, S., Peterson, E., Runinsztaj, R. & Zuckerman, A. (2004). Why we harass nerd and freaks: a formal theory of student culture and norms. Journal of School Health, 74(7). 235-251.

Boyatzis, C. J. Baloff, P. & Durieux, C. (1998). Effects of perceived attractiveness and academic success on early adolescent peer popularity. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 159(3), 337-344.

de Bruyn, E.H. & van den Boom, D. C. (2005). Interpersonal behaviour, peer popularity and self-esteem in early adolescence. Social Development, 14(4). 555- 573.

Deckers, L. (2005). Motivation: Biological, psychological and environmental. (2nd ed.). New York: Allyn & Bacon.

Kosir, K. & Pecjak, S. (2005). Sociometry as a method for investigating peer relationships: what does it actually mean? Educational Research, 47(1), 127-144.

LaFontana , K. M. & Cillessen, A. H. N. (1998). The nature of children’s stereotypes of popularity. Social Development, 7(3), 301-320.

LaFontana , K. M. & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2002). Children’s perceptions of popular and unpopular peers: a multimethod assessment. Developmental Pscyhology, 38(5), 635-674.

Lease, A. M., Kennedy, C. A. & Axelrod, J. L. (2002). Children’s social construction of popularity. Social Development, 11(1), 87-109.

McLellan, J. A. & Pugh, M. J. V. (1999). The Role of Peer Groups in Adolescent Social Identity: Exploring the Importance of Stability and Change. San Francisco; Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Parkhurst, J.T. & Hopmeyer, A. (1998). Sociometric popularity and peer perceived popularity, two distinct dimensions of peer status. The Journal of Early Adolescents, 18(2).

Prinstein, M. J., Meade, C.S., & Cohen, G. L. (2003). Adolescent Oral Sex, Peer Popularity, and Perceptions of Best Friends' Sexual. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 28, (4), 243-249.

Sebald, H. (1992). Adolescents: a Social Psychological Analysis (4th ed). New Jersey; Prentice Hall.

Steinberg, L. (1993). Adolescence (3rd ed.). Sydney; McGraw-Hill, Inc.

Figure 1: Descriptions of Popular and Unpopular Study Targets

Appendix A: Glossary of Terms

Attribution- cognitive process of assigning meaning to a symptom or behaviour (Baumeister & Bushman, 2008, p. 156)

Expressive Equipment: relates to being attractive and having spending power (Lease, Kennedy, & Axelrod, 2002)

In-group- those belonging to the same group “Us” (Baumeister & Bushman, 2008, p. 404)

Normative Influence- Going along with the crowd in order to be liked or accepted (Baumeister & Bushman, 2008, p. 267)

Norms- social standards that prescribe what people ought to do (Baumeister & Bushman, 2008, p. 256)

Out-group- Those belonging to a different group “them” (Baumeister & Bushman, 2008, p. 404)

Reference group- groups that people look to when evaluating or deciding qualities, circumstances, attitudes, values and behaviours (Steinberg, 1993)

Social aggression-consists of actions directed at damaging another's self-esteem, social status, or both, and includes behaviors such as facial expressions of disdain, cruel gossipping, and the manipulation of friendship patterns (Galen & Underwood, 1997).

Social Categorisation- Sorting people into groups on the basis of common characteristics (Baumeister & Bushman, 2008, p. 404)

Social visibility- described as being perceived as ‘cool and athletic’ (Lease, Kennedy, & Axelrod, 2002)

Stereotypes-beliefs that associate groups of people with certain traits (Baumeister & Bushman, 2008, p. 403)

Stigma- an attribute that is perceived by others as broadly negative (Baumeister & Bushman, 2008, p. 227)

Stigma by association- rejection of those who associate with stigmatised others (Baumeister & Bushman, 2008, p. 408)

Definitions from:

Baumeister, R. F., & Bushman, B. J. (2008). Social Psychology and Human Nature (1st ed.) Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

Galen, B. R., & Underwood, M. K. (1998). A developmental investigation of social aggression among children. Developmental Psychology, 33(4), 589-600.

Lease, A. M., Kennedy, C. A. & Axelrod, J. L. (2002). Children’s social construction of popularity. Social Development, 11(1), 87-109.

Steinberg, L. (1993). Adolescence (3rd ed.). Sydney; McGraw-Hill, Inc.

Appendix B: Paradoxical Popularity

Steinberg's (1993) Explanation of Paradoxical Popularity

"There are limits to the number of friendships that anyone person can maintain. Because popular girls get a high number of affiliative offers, they have to reject more offers of friendships than other girls. Also, to maintain their higher status, girls who form the elite group must avoid associations with lower status girls.. These girls are likely to ignore the afflilative attempts of many other girls, leading to the impression that they are stuck-up. Shortly after these girls reach their peak of popularity, they become increasing disliked" (p. 183)

Steinberg, L. (1993). Adolescence (3rd ed.). Sydney; McGraw-Hill, Inc.

Appendix C: Social Competencies of Sociometricly Popular Students

Appendix C: Social Competencies of Sociometricly Popular Students

Some examples of Social Competencies that are described in the Gale Encyclopedia of Child and Adolescents (1998):

- Correctly interpret other children's body language and tone of voice. Well-liked children can distinguish subtleties in emotions. For example, they can distinguish between anger directed toward them versus toward a parent.

- Directly respond to the statements and gestures of other children. Well-liked children will say other children's names, establish eye contact, and use touch to get attention.

- Give reasons for their own statements and gestures (actions). For example, well-liked children will explain why they want to do something the other child does not want to do.

- Cooperate with, show tact towards, and compromise with other children, demonstrating the willingness to subordinate the self by modifying behavior and opinions in the interests of others. For example, when joining a new group where a conversation is already in progress, well-liked children will listen first, establishing a tentative presence in the group before speaking (even if it is to change the subject).

Gale Encyclopedia of Childhood & Adolescence, (1998). [Accessed October 2007]. Peer Acceptance. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_g2602/is_0004/ai_2602000424

Appendix D: Authority, Achievement and Affiliation

Appendix D: Authority, Achievement and Affiliation

Here are a few examples of how McClelland's Theory of Needs could work in a peer relations context

Authority: Students who are popular have domination and prestige. They gain authority through their status. Therefore, one may be motivated to be popular depending on how much they had a high need for authority.

Achievement: Students may want to work their way up in the social scene because they want to achieve more on a social level. If there is a high need for achievement, popular status may be considered a goal

Affiliation- Students want to feel accepted and liked by others. Within schools the status of popularity has many social benefits. Although, peer perceived popularity may not mean that you are liked by all. Therefore those with a drive to be sociometricly popular (liked by others) may have a higher need for affiliation.

Appendix E: Evaluation

Theory

Although I have covered a number of contributing factors to popularity, I feel as though I have not done the topic justice. Due to the extensive amount of research I had to be selective with the information included in the blog. Some areas that could have been covered more includes, cultural age and gender differences. There were many social pyschological variables which related to popularity however the most popular theories were covered only in breif.

With regards to Australian society, I took an approach which was general and could be applied in most western cultures. For example, I did not focus on American groups such as "Jocks" and "Preps" but focused on the general perspective of social interaction between peers. I could have discussed directly relating to Australian society however, I was restricted by some of the Australian articles being avaliable.

Research-

A majority of the research was American however, I feel like I explored research relevant to the questions. I felt satisfied with the amount of research I used and I was able to use journal articles and books to discuss key concepts of the essay.

Online Engagement

I felt satisified with my efforts of online engagement. I contributed to a number of blogs and also posed a number of blogs through out the term. The links can be found below

Blogs posted by me

Special Beauty Report: Erasing Ethnicity

More on Sex...

Sociometrics and popularity-

Popularity- Definition? and a spanner.

Teen Challange Day

SEX and popularity

Which group were you?!

How To...

Friendship, Popularity and Peer Acceptance

POPULARITY!!

Comments on other peoples blogs

Emily's Blog

Amanda's Blog

Rebecca's Blog

Rachels Blog

Emily's Blog

Mikes blog

Zoe's blog

Jess's Blog

Laurens blog

Erins blog

Readability

Word Count- 1,599

Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level: 13.6

Flesch Reading Ease: 27.4